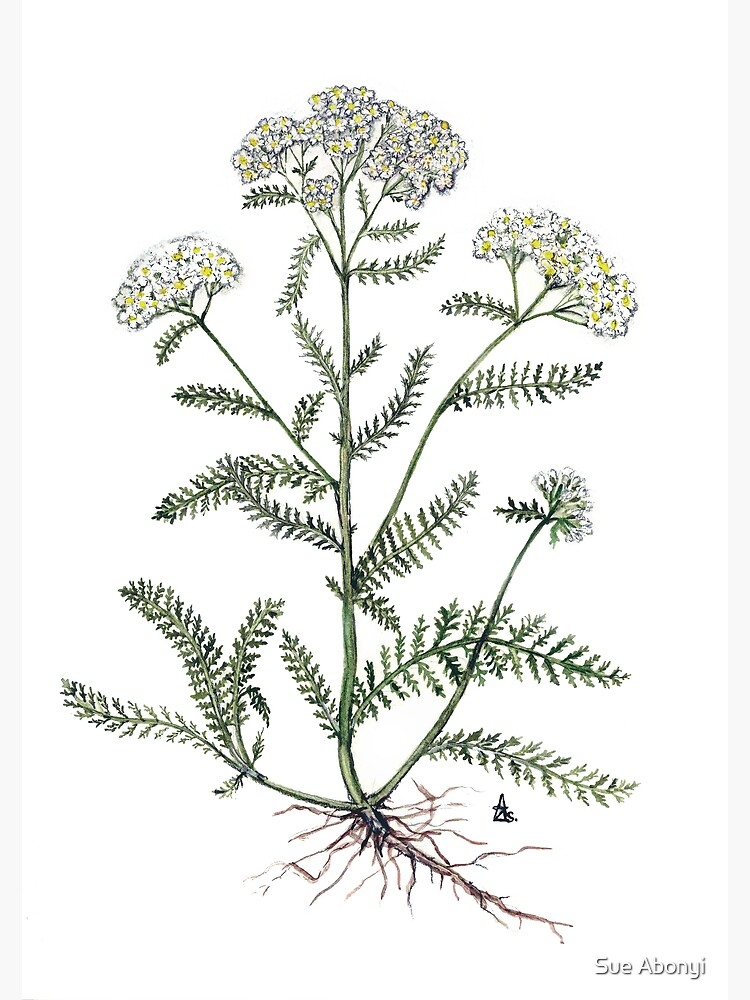

I recently completed organoleptic testing (a method of evaluating herbs using the senses—sight, smell, taste, and touch) on a handful of medicinal plants. Each herb had its own personality, but I wanted to give a special shout-out to one in particular: yarrow (Achillea millefolium).

Yarrow is a fascinating ally—beautifully paradoxical. Soft and lace-like in appearance, she carries within her a warrior’s will. Used traditionally as a wound remedy, she’s still revered today for her ability to tighten tissues, cool heat, stop bleeding, open pores, support healthy digestion, balance menstrual flow, and stimulate immune response. That may sound like a lot—but yarrow, like many herbs, isn’t a one-note healer. She’s a boundary-setter, and her actions reflect that: sealing when needed, releasing when appropriate.

Medicinally, yarrow is considered:

- Astringent – tightening and toning tissues, reducing excessive fluid.

- Styptic – specifically stopping bleeding, both internally and externally.

- Diaphoretic – promoting sweating during fever, assisting in temperature regulation.

- Vulnerary – healing wounds and tissue damage.

- Emmenagogue – stimulating menstrual flow, especially in stagnation.

- Antimicrobial – helping resist bacterial, viral, and fungal invaders.

- Cholagogue and hepatic – encouraging bile flow and supporting liver function.

- Anti-inflammatory and analgesic – reducing pain and swelling.

- Antioxidant, antimutagenic, and even mildly hypotensive.

But these terms, while clinically useful, only tell half the story. Yarrow is a plant you get to know by experience.

🍃 My Organoleptic Journey with Yarrow

Visually, the dried sample was composed of fluffy yellow flower pieces and small, pale, brittle stems. There was a bit of a shimmer to the plant matter that reminded me of dried forage from my rabbit-raising days—sun-cured, familiar, earthy. Many of the flowers were broken down rather than whole, fragmented like they’d been lovingly pestled, their parts ranging from 2 to 4 mm in length. The contrast between the pale stems and golden flowers was striking. I didn’t see any seeds or signs of insects—always a good sign of clean storage and processing.

The scent took me by surprise. I expected something more floral, but what came was dusty, sneezy, and dry—with a subtle sweet undertone that peeked through. I only had to inhale once before my nose began to tickle. It lingered in my sinuses and invited a very literal response: a sneeze. Not unpleasant—just assertive.

Rolling the herb between my fingers, the flower heads felt granular and springy, while the stems were sharper and more rigid. The petals released easily with touch, creating a fine layer of dust. No signs of mold or overdrying—just a well-cured, vibrant plant.

Then came the taste test.

I took a pinch of the dried herb on the tongue, and the yarrow sample was boldly bitter—not a creeping, sneaky bitterness, but an immediate mouth-puckering jolt. My salivary glands sprang to action, trying to dilute the shock. The stems felt sharp, but the fluff of the flower pieces softened the bite. After about a minute, I found myself involuntarily spitting it out—not from disgust, but because my mouth had filled with so much saliva and bitterness that it felt like my body had taken the reins.

What came next was a surprise: a burst of sweet, perfumed floral aroma bloomed across my tongue and up into my sinuses. My mouth tingled and began to dry out again, reinforcing yarrow’s strong astringent nature. A faint numbing sensation lingered on my tongue and cheeks. This was not a shy plant. This was an herb with presence, power, and purpose.

The infusion I brewed was a vibrant, sunflower yellow. The scent reminded me of dill and medicine—sour, savory, and wildly bitter in a medicinal kind of way. The taste was… So bitter. Almost overwhelmingly so. My face scrunched. My eyebrows puckered. I felt a pulse of tension in my temples and the faint echo of a headache I had been ignoring. Yet it wasn’t entirely offensive—it was activating. Yarrow doesn’t sit back. It pulls you forward, sharpens your senses, and demands attention.

🌸 Why Yarrow?

Yarrow is fascinating because it lives in the threshold—between blood and skin, warmth and sweat, tension and flow. It’s a boundary herb, both physically and energetically. I reach for yarrow when there’s stagnation, dull heat, or excess—whether it’s a fever, sluggish digestion, or a menstrual cycle that needs coaxing. It’s also a plant I call on when I need to tighten the edges of myself, energetically speaking.

It isn’t a gentle tea you sip to relax. It’s a powerful herbal presence. For those looking to reconnect with the deeper intelligence of plant medicine, yarrow offers not just healing, but initiation.

Medicinal purposes that may benefit from a little yarrow include stimulating appetite, coughs, colds, fevers, influenza, inflammatory disorders, measles, oral ulcers, and bronchitis. Yarrow is a useful support for patients undergoing chemotherapy, and can aid diabetics, as well as those suffering from angina or hypertension.

For menstrual troubles, yarrow is a useful remedy for menorrhagia, dysmenorrhea, and amenorrhea, and can even help patients with vaginal thrush.

The astringent and styptic effects of yarrow flowers are also useful for hemorrhoids and internal or external hemorrhage, as well as general wound healing and even nosebleeds.

Kidney stones and “a sluggish liver” area are also specific for A. millefolium. As a powerful bitter and astringent, yarrow aids in digestion and helps with stomach gas, can dry out oral ulcers and stimulate faster healing, and can even be used topically to balance the skin’s pH.

⚠️ A Note on Achillea millefolium and Safety

Achillea millefolium is a strong herbal ally, and like many potent herbs, it should be used with awareness. People who are pregnant or lactating should avoid high doses, though small culinary amounts are generally safe. Those allergic to the Asteraceae family (like ragweed) should also use yarrow cautiously. Always check for potential interactions with medications, especially those that rely on liver detoxification pathways (such as acetaminophen), as yarrow can influence glutathione metabolism.

And of course, the bitter taste can be overwhelming to some—so if you’re new to this herb, start with small amounts or pair it with other, more palatable botanicals.